The Patient-Centered Dosing Initiative: Personalization. Communication. Innovation.

Have you been dealing with side effects from your metastatic breast cancer treatment? If so, you are not alone.

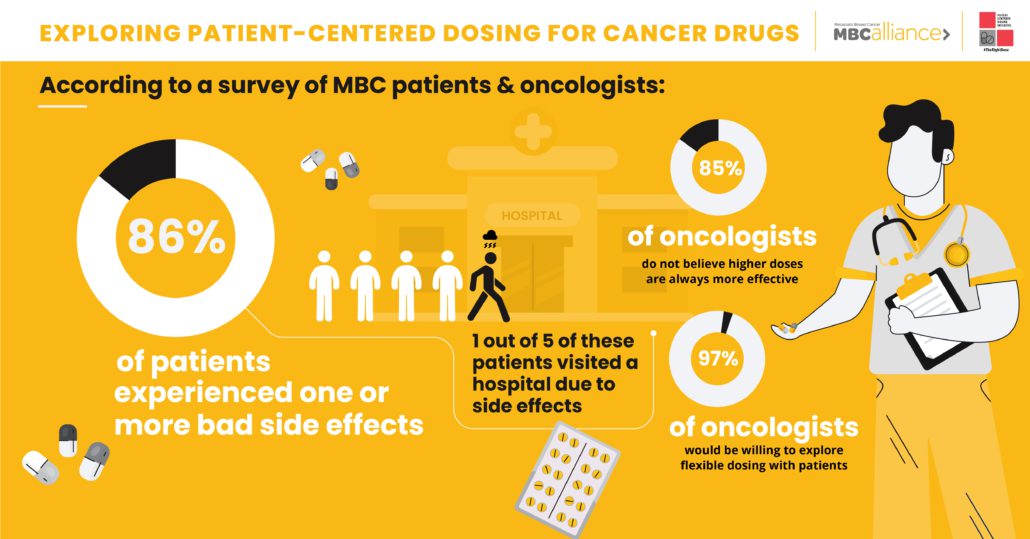

An MBC Patient Survey recently conducted by the Patient Centered Dosing Initiative (PCDI) found that out of 1,221 respondents, 86% had experienced at least one bad side effect related to their cancer drug. Of these, 1 out of 5 had visited the hospital and more than 2 out of 5 missed at least one scheduled treatment due to those side effects.

That’s a dynamic PCDI founder Anne Loeser wants to change.

Is more really better when it comes to cancer drug dosing?

An MBC patient advocate first diagnosed with early stage breast cancer at age 39, Anne herself endured considerable side effects from her treatments. In learning more about how cancer drug dosing works, she realized there was a key driver behind the high level of severe side effects reported by her peers: clinical trials and dosing guidelines for cancer drugs are still being based on an outdated assumption.

“The cancer drug-dosing paradigm that has been with us for 70 years can be summed up in three words: More is better,” says Anne. “It’s been assumed all along that efficacy and toxicity increase with higher dosage.”

Since the era of cytotoxic chemotherapy drug development, Phase I clinical trials for cancer drugs have measured the maximum tolerated dose patients can endure with what are deemed to be “acceptable” side effects. And as drugs are approved to market, the recommended starting dose is generally based upon this maximum tolerated dose as a result of the premise that aggressive treatment will lead to better outcomes.

But, Anne notes, Phase I trials do not measure efficacy levels or long-term side effects. And a growing body of evidence is calling into question the “more is better” philosophy.

One high-profile example dating back to 2000 was a trial showing that, of 41,000 breast cancer patients who received high-dose chemotherapy in tandem with a bone marrow transplant, there was no survival advantage compared to patients who received standard-dose chemotherapy. But without question, there was a vast impact to quality of life for patients enduring the more aggressive treatment.

And for Anne and her fellow MBC community members, that difference can be crucial. Because MBC is considered treatable but not curable, most people living with the disease will remain on cancer drugs for the rest of their lives. As their current line of therapy gradually stops working, they must seek out new lines of therapy.

Access to drugs with less severe side effects may enable those living with MBC to remain on a working therapy longer, take fuller advantage of the treatments available to them, and miss fewer treatments. Furthermore, patients may potentially live longer with better quality of life.

That’s why, through the Patient-Centered Dosing Initiative, Anne and her peers are working to elevate the conversation around why it remains the default to treat MBC patients with the maximum tolerated dose of cancer drugs – a practice that means that patients moving to a new drug are generally prescribed the most toxic dose with the most challenging side effects at the beginning of each new regimen.

Rather than continue the above practice, the PCDI advocates for physicians to consult with patients when discussing drug dosages upon treatment initiation and throughout treatment, taking into account the patient’s personal wishes and unique characteristics such as age, availability of at-home care, history of side effects and more.

The vision of shifting an entire field from a one-size-fits-all process to a tailored patient-centered dosing model seems like a heavy lift. But research done through PCDI has shown this change may already be beginning.

Bringing patient voices into MBC drug dosing decisions

In addition to surveying MBC patients about their experience with side effects of cancer treatments, the PCDI also conducted a Medical Oncologists Survey for US-based providers who have experience in treating MBC.

Not surprisingly, the oncologists somewhat underestimated the prevalence and severity of cancer drug side effects when measured against self-reported patient responses. But the survey did yield some unexpected – and very positive – results from the oncologists surveyed: 85% of surveyed oncologists did not believe that a higher dose of a cancer drug is always more effective than a lower dose, and 97% said they would be willing to discuss flexible dosing with their patients.

The results from the surveys conducted by the PCDI are already serving as a catalyst for transformation. The FDA recently introduced Project Optimus, an initiative aimed at reforming the decades-old paradigm of identifying the maximum tolerable dose of a drug in Phase 1 clinical trials. Through the new initiative, future Phase 1 clinical trials will aim to identify dosing guidelines based on a combination of efficacy, tolerability, and safety, with the goal of enabling patients to better tolerate treatments.

Another FDA initiative called Project Renewal is aimed at updating labeling information for certain older cancer drugs with the objective of ensuring that the information is clinically meaningful and scientifically current. Under Project Renewal, the oral chemotherapy drug capecitabine (Xeloda) has been the first drug to receive a dosage-related label update to render it more tolerable.

For Anne and the PCDI, the introduction of Project Optimus and Project Renewal represents a huge step in the right direction. But while changes in dosing standards could transform the experience of future MBC patients, she notes that there’s still a long way to go before it’s standard practice for oncologists to partner with patients to prescribe a drug dose based on individual characteristics and personal wishes.

For those navigating the challenges of MBC in the here and now, Anne says the best first step is self-empowerment through knowledge.

“Our biggest challenge is changing and transforming clinical practice,” says Anne. “Shifting that experience when we walk into the doctor’s office is extremely hard. Creating awareness about the severity and prevalence of treatment-related issues is our first step.”

To learn more about the Patient-Centered Dosing Initiative or to become involved, please contact info@therightdose.org.